Packer

aws-get-started

This post is the alternative of Getting Started with AWS and Provision Infrastructure with Packer, whose contents have been closed sourced by HashiCorp.

HashiCorp Packer automates the creation of any type of machine image, including AWS AMIs. You'll build an Ubuntu machine image on AWS in this tutorial.

Install Packer

macOS

$ brew tap hashicorp/tap

$ brew install hashicorp/tap/packer

Build an Image

With Packer installed, it is time to build your first image. In this tutorial, we will build a t2.micro

Amazon EC2 AMI.

Note: This tutorial will provision resources that qualify under the AWS free-tier. If our account doesn't qualify under the AWS free-tier, Packer is not responsible for any charges that may incur.

Write Packer Template

A Packer template is a configuration file that defines the image we want to build and how to build it. Packer templates use the Hashicorp Configuration Language (HCL).

HashiCorp has a comprehensive tutorial on how to build an image and deploys an instance of that image to AWS. The tutorial introduces a standard directory structure for storing HashiCorp related files. This structure can be found in their tutorial code repo. We will be using that as our reference file structure:

.

└── my-app/

├── hashicorp/

│ ├── images/

│ │ ├── aws-my-app.pkr.hcl

│ │ └── variables.pkr.hcl

│ ├── instances/

│ │ └── main.tf

│ └── scripts/

│ └── script.sh

├── src

└── ...

The images/ contains Packer related files

- The scripts/ directory has the post-build script for the AMI image, which we will cover later

The instances/ contains Terraform related files

Create the file aws-my-ami.pkr.hcl and add the following HCL block to it, and save the file.

packer {

required_plugins {

amazon = {

version = ">= 0.0.2"

source = "github.com/hashicorp/amazon"

}

}

}

source "amazon-ebs" "my-ami" {

ami_name = "my-ami"

force_deregister = "true"

force_delete_snapshot = "true"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

region = "us-west-1"

source_ami_filter {

filters = {

name = "ubuntu/images/*ubuntu-*-20.04-amd64-server-*"

root-device-type = "ebs"

virtualization-type = "hvm"

}

most_recent = true

owners = ["099720109477"]

}

ssh_username = "ubuntu"

}

build {

name = "install-my-ami"

sources = [

"source.amazon-ebs.my-ami"

]

provisioner "shell" {

environment_vars = [

"GH_PAT_READ=${var.gh_pat_read}"

]

script = "../scripts/setup.sh"

}

}

This is a complete Packer template that we will use to build an AWS Ubuntu AMI in the us-west-1 region. In the

following sections, we will review each block of this template in more detail.

Packer Block

The `packer {} block contains Packer settings, including specifying a required Packer version.

In addition, we will find required_plugins block in the Packer block, which specifies all the plugins required by the template to build our image. Even though Packer is packaged into a single binary, it depends on plugins for much of its functionality. Some of these plugins, like the Amazon AMI Builder (AMI builder) which we will to use, are built, maintained, and distributed by HashiCorp; but anyone can write and use plugins.

Each plugin block contains a version and source attribute. Packer will use these attributes to download the appropriate plugin(s).

- The source attribute is only necessary when requiring a plugin outside the HashiCorp domain. We can find the full list of HashiCorp and community maintained builders plugins in the Packer Builders documentation page.

- The version attribute is optional, but we recommend using it to constrain the plugin version so that Packer does not install a version of the plugin that does not work with our template. If we do not specify a plugin version, Packer will automatically download the most recent version during initialization.

In the example template above, Packer will use the Packer Amazon AMI builder plugin that is greater than version 0.0.2.

Source Block

The source block configures a specific builder plugin, which is then invoked by a build block. Source blocks use builders and communicators to define what kind of virtualization to use, how to launch the image we want to provision, and how to connect to it. Builders and communicators are bundled together and configured side-by-side in a source block. A source can be reused across multiple builds, and we can use multiple sources in a single build. A builder plugin is a component of Packer that is responsible for creating a machine and turning that machine into an image.

A source block has two important labels: a builder type and a name. These two labels together will allow us to uniquely

reference sources later on when we define build runs. In the example template above, the builder type is amazon-ebs

and the name is my-ami.

Each builder has its own unique set of configuration attributes. The amazon-ebs builder launches the source AMI, runs provisioners within this instance, then repackages it into an EBS-backed AMI.

In the example template, the amazon-ebs builder configuration launches a t2.micro AMI in the us-west-1 region

using an ubuntu:20.04 AMI as the base image, then creates an image named "my-ami" from that instance. The builder

will create all the temporary resources necessary (for example, keypairs, security group rules, etc..) to temporarily

access the instance while the image is being created.

Note that the

owners = ["099720109477"]is the "owner" who publishes the Ubuntu AMI image, not the image ID

This example template also uses the SSH communicator. By specifying the ssh_username attribute, Packer is able to SSH into EC2 instance using a temporary keypair and security group to provision our instances.

About

force_deregister = "true"&force_delete_snapshot = "true"Force Packer to first deregister an existing AMI if one with the same name already exists; then delete snapshots associated with AMIs, which have been deregistered by

force_deregister. This is very important because otherwise Packer fails by complaining that AMI with the same name is already there. In addition, we don't have to worry about cleaning up AMI on AWS; we simply keep AMI version controlled as code rather than a hard-to-main AMI infrastructures. See this post and Packer doc for more info

The Build Block

The build block defines what Packer should do with the EC2 instance after it launches.

In the example template, the build block references the AMI defined by the source block above

(source.amazon-ebs.my-ami).

build {

sources = [

"source.amazon-ebs.ubuntu"

]

}

Provisioners

Historically, pre-baked images have been frowned upon because changing them was so tedious and slow. Because Packer is completely automated (including provisioning) images can be changed quickly and integrated with modern configuration management tools such as Chef or Puppet. Using provisioners allow us to do exactly for that

Notice that the source.amazon-ebs.my-ami uses the SSH communicator. By specifying the

ssh_username attribute, Packer is able to SSH into EC2 instance using a temporary keypair and security group to

provision our instances.

source "amazon-ebs" "my-ami" {

## ...

ssh_username = "ubuntu"

}

Our provisioner block is in our Packer template, inside the build block and underneath the sources assignment:

build {

...

provisioner "shell" {

environment_vars = [

"GH_PAT_READ=${var.gh_pat_read}"

]

script = "../scripts/setup.sh"

}

}

This block defines a shell provisioner which sets an environment variable named GH_PAT_READ

in the shell execution environment and runs the script at a specified relative path. The

environment_vars

option is used to pass argument into the provisioner script so that the script can reference it via $GH_PAT_READ:

#!/bin/bash

set -x

sudo apt update && sudo apt upgrade -y

sudo apt install software-properties-common -y

sudo add-apt-repository ppa:deadsnakes/ppa

sudo apt install python3.10 -y

sudo apt install python3-pip -y

git clone https://$GH_PAT_READ@github.com/MyGitHub/my-app.git

cd /home/ubuntu/my-app

sudo pip3 install .

The script, when IAM image is up for customization, installs some system dependencies, clones some repositories, and setup the app in the script. Note that the repository clone uses the GitHub PAT token, which we pass in

We've passed dynamic data from Template file into our provisioner script. However, our Packer template is usually run in some CI/CD process and those dynamic data usually originate from the CI/CD configurations. How do we pass those configurations into the Packer build/template then?

We can use input variables to serve as parameters for a Packer build, allowing aspects of the build to be customized without altering Packer template. In addition, Packer variables are useful when we want to reference a specific value throughout our template. To do that, we have the following variable block in our hashicorp/images/variables.pkr.hcl file::

variable "gh_pat_read" {

type = string

sensitive = true

}

Authenticating to AWS

Before we can build the AMI, we need to provide our AWS credentials to Packer. These credentials have permissions to create, modify and delete EC2 instances. Refer to the documentation to find the full list IAM permissions required to run the amazon-ebs builder.

To allow Packer to access our IAM user credentials, set our AWS access key ID as an environment variable.

$ export AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID="<YOUR_AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID>"

$ export AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY="<YOUR_AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY>"

Note: If we don't have access to IAM user credentials, use another authentication method described in the Packer documentation.

Initialize Packer Configuration

$ packer init .

Installed plugin github.com/hashicorp/amazon v0.0.2 in "/Users/youruser/.packer.d/plugins/github.com/hashicorp/amazon/packer-plugin-amazon_v0.0.2_x5.0_darwin_amd64"

Packer will download the plugin we've defined above. In this case, Packer will download the Packer Amazon plugin that is greater than version 0.0.2. We can run packer init as many times as you'd like. If we already have the plugins we need, Packer will exit without an output.

Packer has now downloaded and installed the Amazon plugin. It is ready to build the AMI!

Formatting and Validating Packer Template

We recommend using consistent formatting in all template files. The packer fmt command updates templates in the current directory for readability and consistency.

By formatting our template. Packer will print out the names of the files it modified, if any. In this case, our template file was already formatted correctly, so Packer won't return any file names.

$ packer fmt .

We can also make sure our configuration is syntactically valid and internally consistent by using the packer validate command. If Packer detects any invalid configuration, Packer will print out the file name, the error type and line number of the invalid configuration. The example configuration provided above is valid, so Packer will return nothing.

$ packer validate .

Building Packer Image

Build the image with the packer build command. Packer will print output similar to what is shown below.

$ packer build aws-my-ami.pkr.hcl

learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: output will be in this color.

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Prevalidating any provided VPC information

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Prevalidating AMI Name: learn-packer-linux-aws

learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Found Image ID: ami-0dd273d94ed0540c0

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Creating temporary keypair: packer_608a6435-e0b2-c633-95f0-bf168f01e891

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Creating temporary security group for this instance: packer_608a6437-6b48-288e-6d5e-c085366a5541

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Authorizing access to port 22 from [0.0.0.0/0] in the temporary security groups...

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Launching a source AWS instance...

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Adding tags to source instance

learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Adding tag: "Name": "Packer Builder"

learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Instance ID: i-023d696a318e9594c

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Waiting for instance (i-023d696a318e9594c) to become ready...

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Using ssh communicator to connect: 35.166.142.55

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Waiting for SSH to become available...

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Connected to SSH!

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Stopping the source instance...

learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Stopping instance

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Waiting for the instance to stop...

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Creating AMI learn-packer-linux-aws from instance i-023d696a318e9594c

learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: AMI: ami-0703a21445140541e

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Waiting for AMI to become ready...

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Terminating the source AWS instance...

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Cleaning up any extra volumes...

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: No volumes to clean up, skipping

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Deleting temporary security group...

==> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu: Deleting temporary keypair...

Build 'learn-packer.amazon-ebs.ubuntu' finished after 3 minutes 5 seconds.

==> Wait completed after 3 minutes 5 seconds

==> Builds finished. The artifacts of successful builds are:

--> learn-packer.amazon-ebs.my-ami: AMIs were created:

us-west-2: ami-0703a21445140541e

Now visit the AWS AMI page to verify that Packer successfully built your AMI.

Managing the Image

Packer only builds images. It does not attempt to manage them in any way. After they're built, it is up to us to launch or destroy them as we see fit.

After running the example above, our AWS account now has an AMI associated with it. AMIs are stored in S3 by Amazon so we may be charged.

We can remove the AMI by first deregistering it on the AWS AMI management page. Next, delete the associated snapshot on the AWS snapshot management page.

Deploying Packer Image with Terraform

Install Terraform

We have seen Packer as HashiCorp's open-source tool for creating machine images from source configuration. We can configure Packer images with an operating system and software for our specific use-case.

Terraform configuration for a compute instance can use a Packer image to provision our instance without manual configuration.

In this section, we will deploy the AMI image we just created using Terraform.

macOS

$ brew tap hashicorp/tap

$ brew install hashicorp/tap/terraform

Building Infrastructure

Writing Configuration

To use the AMI in our Terraform environment, navigate to the instances directory (Each Terraform configuration must be in its own working directory. Create a directory for your configuration).

$ cd hashicorp/instances

Create a main.tf file with the following contents:

terraform {

required_providers {

aws = {

source = "hashicorp/aws"

version = "~> 4.42.0"

}

}

required_version = ">= 0.14.5"

}

provider "aws" {

region = "us-west-1"

}

data "aws_ami" "latest-my-ami" {

most_recent = true

owners = ["255643778305"]

filter {

name = "name"

values = ["my-ami"]

}

filter {

name = "virtualization-type"

values = ["hvm"]

}

}

resource "aws_instance" "my-ami-instance" {

ami = "${data.aws_ami.latest-my-ami.id}"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

user_data = <<-EOF

#!/bin/bash

cd /home/ubuntu/my-ami

# command that starts app, e.g. flask --app server run --host=0.0.0.0

EOF

}

The file above in Terraform is known as a Terraform configuration. The following sections review each block of this configuration in more detail.

Hands-on: Getting the Latest AWS AMI ID with Terraform using data block and AWS API

This is a great time saver, it stops us from having to hard code any AMI IDs within Terraform. This solution will also enable us to get the latest AMIs in the region we are working in by dynamically querying the AWS API. Good stuff!

Terraform Block

The terraform {} block contains Terraform settings, including the required providers Terraform will use to provision our infrastructure. For each provider, the source attribute defines an optional hostname, a namespace, and the provider type. Terraform installs providers from the Terraform Registry by default. In this example configuration, the aws provider's source is defined as hashicorp/aws, which is shorthand for registry.terraform.io/hashicorp/aws.

We can also set a version constraint for each provider defined in the required_providers block. The version attribute is optional, but we recommend using it to constrain the provider version so that Terraform does not install a version of the provider that does not work with our configuration. If we do not specify a provider version, Terraform will automatically download the most recent version during initialization.

To learn more, please reference the provider source documentation.

Providers

The provider block configures the specified provider, in this case aws. A provider is a plugin that Terraform

uses to create and manage our resources.

We can use multiple provider blocks in our Terraform configuration to manage resources from different providers. We can even use different providers together. For example, we could pass the IP address of our AWS EC2 instance to a monitoring resource from DataDog.

Resources

Use resource blocks to define components of our infrastructure. A resource might be a physical or virtual component such as an EC2 instance, or it can be a logical resource such as a Heroku application.

Resource blocks have two strings before the block: the resource type and the resource name. In this example, the

resource type is aws_instance and the name is my-ami-instance. The prefix of the type maps to the name of the

provider. In the example configuration, Terraform manages the awsinstance resource with the aws provider. Together,

the resource type and resource name form a unique ID for the resource. For example, the ID for your EC2 instance is

_aws_instance.my-ami-instance.

Resource blocks contain arguments which we use to configure the resource. Arguments can include things like machine sizes, disk image names, or VPC IDs. HashiCorp's providers reference lists the required and optional arguments for each resource. For our EC2 instance, the example configuration sets the AMI ID to our my-ami image we created above, and the instance type to t2.micro, which qualifies for AWS' free tier. It also sets a tag to give the instance a name.

We are also baking a startup script directly into the creation of our EC2 instance using Terraform. We do that using an inline bash script specified in the user_data parameter that, for example, starts a web server.

Initializing the Directory

When we create a new configuration - or check out an existing configuration from version control - we need to initialize the directory with terraform init.

Initializing a configuration directory downloads and installs the providers defined in the configuration, which in this case is the aws provider.

$ terraform init

Initializing the backend...

Initializing provider plugins...

- Finding hashicorp/aws versions matching "~> 4.16"...

- Installing hashicorp/aws v4.17.0...

- Installed hashicorp/aws v4.17.0 (signed by HashiCorp)

Terraform has created a lock file .terraform.lock.hcl to record the provider

selections it made above. Include this file in your version control repository

so that Terraform can guarantee to make the same selections by default when

you run "terraform init" in the future.

Terraform has been successfully initialized!

You may now begin working with Terraform. Try running "terraform plan" to see

any changes that are required for your infrastructure. All Terraform commands

should now work.

If you ever set or change modules or backend configuration for Terraform,

rerun this command to reinitialize your working directory. If you forget, other

commands will detect it and remind you to do so if necessary.

Terraform downloads the aws provider and installs it in a hidden subdirectory of our current working directory, named

.terraform. The terraform init command prints out which version of the provider was installed. Terraform also creates

a lock file named .terraform.lock.hcl which specifies the exact provider versions used, so that we can control when

we want to update the providers used for our project.

Formatting and validating the Configuration

We recommend using consistent formatting in all configuration files. The terraform fmt command automatically updates configurations in the current directory for readability and consistency.

By formatting our configuration, terraform will print out the names of the files it modified, if any. In this case, our configuration file was already formatted correctly, so Terraform won't return any file names.

$ terraform fmt

We can also make sure our configuration is syntactically valid and internally consistent by using the terraform validate command:

$ terraform validate

Success! The configuration is valid.

Creating Infrastructure

Apply the configuration now with the terraform apply command. Terraform will print output similar to what is shown below. We have truncated some of the output to save space.

terraform apply

Terraform used the selected providers to generate the following execution plan.

Resource actions are indicated with the following symbols:

+ create

Terraform will perform the following actions:

aws_instance.app_server will be created

+ resource "aws_instance" "app_server" {

+ ami = "ami-830c94e3"

+ arn = (known after apply)

#...

Plan: 1 to add, 0 to change, 0 to destroy.

Do you want to perform these actions?

Terraform will perform the actions described above.

Only 'yes' will be accepted to approve.

Enter a value:

Before it applies any changes, Terraform prints out the execution plan which describes the actions Terraform will take in order to change our infrastructure to match the configuration.

The output format is similar to the diff format generated by tools such as Git. The output has a + next to

aws_instance.my-ami-instance, meaning that Terraform will create this resource. Beneath that, it shows the attributes

that will be set. When the value displayed is (known after apply), it means that the value will not be known until

the resource is created. For example, AWS assigns Amazon Resource Names (ARNs) to instances upon creation, so Terraform

cannot know the value of the arn attribute until we apply the change and the AWS provider returns that value from the

AWS API.

Terraform will now pause and wait for your approval before proceeding. If anything in the plan seems incorrect or dangerous, it is safe to abort here before Terraform modifies your infrastructure.

In this case the plan is acceptable, so type "yes" at the confirmation prompt to proceed. Executing the plan will take a few minutes since Terraform waits for the EC2 instance to become available.

Enter a value: yes

aws_instance.app_server: Creating...

aws_instance.app_server: Still creating... [10s elapsed]

aws_instance.app_server: Still creating... [20s elapsed]

aws_instance.app_server: Still creating... [30s elapsed]

aws_instance.app_server: Creation complete after 36s [id=i-01e03375ba238b384]

Apply complete! Resources: 1 added, 0 changed, 0 destroyed.

Hands-on: To execute Terraform actions without the interactive prompt (for example, in a CI/CD environment), use

terraform apply -auto-approve

(Initial Deployment Only) Inspect Instance

We would normally undergo lots of debugging and tuning for our first app deployment by ssh into the EC2 instance. Terraform can generate SSL/SSH private keys using the tls_private_key resource.

So if we wanted to generate SSH keys on the fly we could do something like this (this behavior is not in the example configuration above):

resource "tls_private_key" "example" {

algorithm = "RSA"

rsa_bits = 4096

}

resource "aws_key_pair" "generated_key" {

key_name = "initial-deployment-tuning-ssh-key"

public_key = tls_private_key.example.public_key_openssh

}

...

resource "aws_instance" "my-ami-instance" {

ami = "${data.aws_ami.latest-my-ami.id}"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

key_name = aws_key_pair.generated_key.key_name

user_data = <<-EOF

#!/bin/bash

cd /home/ubuntu/my-ami

# command that starts app, e.g. flask --app server run --host=0.0.0.0

EOF

}

output "private_key" {

value = tls_private_key.example.private_key_pem

sensitive = true

}

This will create an SSH key pair that lives in the Terraform state (it is not written to disk in files other than what might be done for the Terraform state itself when not using remote state), creates an AWS key pair based on the public key and then creates an Ubuntu 20.04 instance where the ubuntu user is accessible with the private key that was generated.

We would then have to extract the private key from the state file for us to use in ssh command. We could use an

output to spit this straight out to stdout when Terraform is applied by

$ terraform output -raw private_key

Security caveats: It should be pointed out here that passing private keys around is generally a bad idea and we'd be much better having developers create their own key pairs and provide others with the public key that people (or them) can use to generate an AWS key pair (potentially using the aws_key_pair resource as used in the above example) that can then be specified when creating instances. In general we should only use something like the above way of generating SSH keys for very temporary dev environments that we are controlling so we don't need to pass private keys to anyone. If we do need to pass private keys to people we will need to make sure that we do this in a secure channel and that we make sure the Terraform state (which contains the private key in plain text) is also secured appropriately.

To Log in with the SSH private key we obtained above,

nano private-key.pem

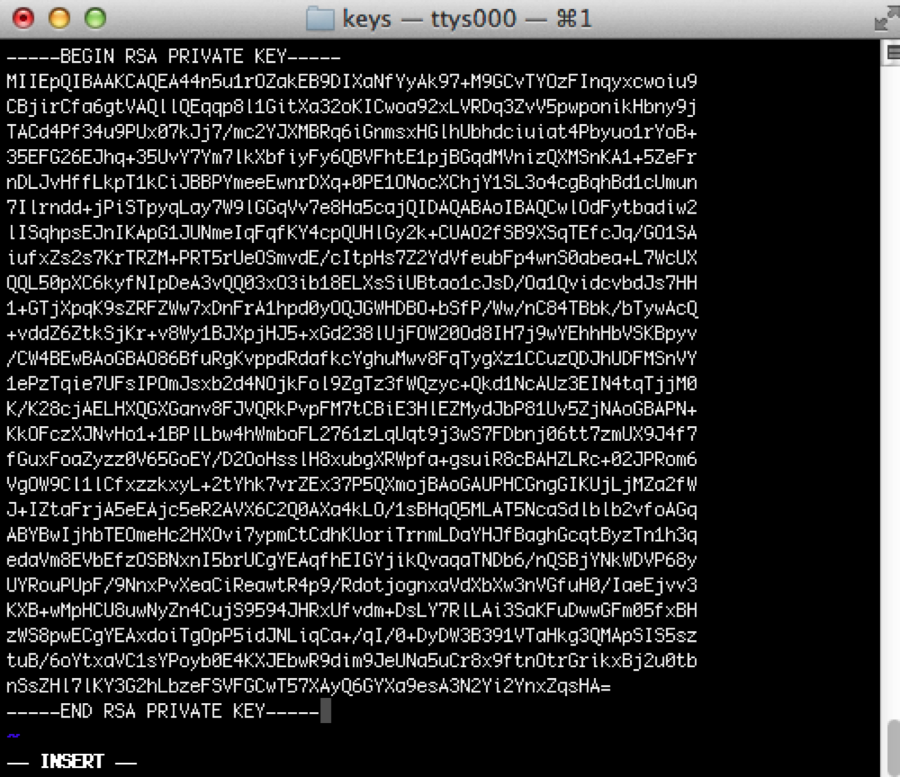

Paste private key, such as the one in the following image, into the file. Be sure to include the BEGIN and END lines.

Run the following command to change the file permissions to 600 to secure the key. We can also set them to 400. This step is required:

chmod 600 private-key.pem

Use the key to log in to the SSH client as shown in the following example, which loads the key in file private-key.pem, and logs in as userubuntu to IP 192.237.248.66:

ssh -i private-key.pem ubuntu@192.237.248.66

GitHub Actions

---

name: My App CI/CD

on:

pull_request:

branches:

- master

push:

branches:

- master

env:

HASHICORP_PRODUCT_VERSION: "latest"

jobs:

release:

name: Release IAM image to AWS and Deploys instance to EC2

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

defaults:

run:

working-directory: hashicorp

steps:

- name: Checkout

uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: Configure AWS credentials

if: github.ref == 'refs/heads/master'

uses: aws-actions/configure-aws-credentials@v1

with:

aws-access-key-id: ${{ secrets.AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID }}

aws-secret-access-key: ${{ secrets.AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY }}

aws-region: us-west-1

- name: Setup HashiCorp Packer

uses: hashicorp/setup-packer@main

with:

version: ${{ env.HASHICORP_PRODUCT_VERSION }}

- name: Initialize Packer configuration

run: packer init .

working-directory: hashicorp/images

- name: Validate Packer template

run: packer validate -var "gh_pat_read=${{ secrets.GH_PAT_READ }}" .

working-directory: hashicorp/images

- name: Build and release AMI image

if: github.ref == 'refs/heads/master'

run: packer build -var "gh_pat_read=${{ secrets.GH_PAT_READ }}" .

working-directory: hashicorp/images

- name: Setup HashiCorp Terraform

uses: hashicorp/setup-terraform@v2

with:

terraform_version: ${{ env.HASHICORP_PRODUCT_VERSION }}

- name: Initialize Terraform configuration

run: terraform init

working-directory: hashicorp/instances

- name: Validate Terraform template

run: terraform validate

working-directory: hashicorp/instances

- name: Create EC2 instance

if: github.ref == 'refs/heads/master'

run: terraform apply -auto-approve

working-directory: hashicorp/instances

Note that to get the aforementioned debugging private key, we would change the last step from

run: terraform apply -auto-approve

to

run: terraform apply -auto-approve && terraform output -raw private_key